Rosenstrasse:

Rosenstrasse:[Varian Fry Institute] [Chambon Foundation Home] [Chambon Institute Home]

Rosenstrasse:

Rosenstrasse:

Resistance of the Heart

a onetime Chambon Foundation production

photograph by Abraham Pisarek

The

Chambon Foundation has regretfully abandoned plans for a one-hour documentary based on Resistance of the Heart: Intermarriage and the

Rosenstrasse Protest in Nazi Germany (W. W. Norton, 1996, paperback edition

Rutgers University Press, March

2001), Nathan Stoltzfus’ highly acclaimed study of the

demonstrations in Berlin in 1943 that defied the Gestapo and succeeded in

reversing a planned deportation of Jews.

The effort, led by mainly by

women--non-Jewish spouses in intermarried relationships--hauntingly suggests

that direct challenges to the Final Solution were not necessarily doomed to

failure.

A dozen interviews of Rosenstrasse participants

were videotaped and will be made available in the future for posterity.

In Germany, according to author Stoltzfus, it is commonly believed that it was impossible for Germans to resist the dictatorship in Nazi Germany. This has grown to constitute the ultimate alibi: “What could we have done?”

To be sure, it wasn't easy for an “ordinary person” to stand in the way of the Holocaust. And yet, a little-known street protest in early 1943 shows that German resistance to the deportation of German Jews was not necessarily doomed. Indeed, the gathering on Rosenstrasse—the only known public German protest against the deportation of Jews—stunningly achieved its aims. Ordinary Germans—mostly women, as it happens—stood up to the Third Reich and won!

In

Weapons of the Spirit,

Not Idly By—Peter

Bergson, America and the Holocaust, and the upcoming

And

Crown Thy Good, Pierre Sauvage and the Chambon

Foundation have focused on the few who cared during those terrible times, and

underscored how the actions of French villagers and a few singular Americans

raise the most fundamental questions about individual and national choices

during that turning point in history.

Rosenstrasse:

Resistance of the Heart would have continued and deepened that approach by entering “the belly

of the beast.” Combining

the Chambon Foundation's consistently challenging approach with Stoltzfus’ unparalleled

scholarship on the Rosenstrasse

protest, this documentary such a documentary could convey a new and fundamental understanding of the

nature of German responsibility for the singular evil of the Holocaust,

underscoring the individual responsibility all citizens share in the actions of

their governments.

Among the questions a Rosenstrasse documentary couldl address are the following:

Who were these people who dared to protest against one of history's most ruthless regimes?

What was source of their determination to overcome?

Why did the Nazis “blink”?

Was resistance to the massacre of the Jews indeed possible, even in the heart of Germany?

Could it be that the Nazis did pay scrupulous attention to popular opinion within Germany, contrary to what has often been assumed?

Was the social isolation imposed by fellow Germans on the Jews a major factor in making the Holocaust possible?

What are the timeless implications for citizens of all nations?

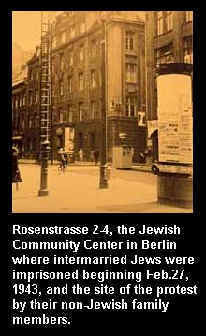

The basic facts are simply stated.

Up until early 1943, Jews married to Germans had been exempted from the

death camp deportations. But during

what the Gestapo called the “Final Roundup of Jews,” they too were arrested

and taken to a pre-deportation collection center at Rosenstrasse

2-4, in the heart of Berlin, and the key location for this documentary.

Most of these mixed marriages involved Jewish men married to non-Jewish

women. The German women quickly

discovered this collection center, and began to meet each other there. Soon they

began calling out in one voice, "Give us our husbands back."

As many as 600 or more gathered together that first day, and

as many as 6,000 may have joined in at various times as the protests grew day

after day, for a week. Again and

again, the police scattered the women with threats to shoot them down in the

streets, but each time they advanced again, with increasing solidarity although

they were unarmed, unorganized and leaderless.

It is hard to imagine an act more dangerous for German civilians than an

open confrontation with the Gestapo, on the Gestapo's front doorstep.

Arrest seemed a foregone conclusion.

“Without warning, the guards began setting up machine

guns,” Charlotte Israel recalled. “Then

they directed them at the crowd and shouted: ‘If you don’t go now, we’ll

shoot.’ The movement surged

backward. But then, for the first

time, we really hollered. Now, we

couldn’t care less. They’re

going to shoot in any case, so now we’ll yell too, we thought.

We yelled, ‘Murderer, murderer, murderer, murderer.’”

Joseph Goebbels, in addition to being the influential

Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, also served as Gauleiter

(Nazi Party Leader) of Berlin. “There

have been unpleasant scenes,” he noted in his diary. “The people gathered together in large throngs and even sided with the

Jews to some extent.” Astonishingly,

after a week of this, Goebbels suddenly ordered the release of the Jews with

German spouses, for reasons that provide key insights into the nature of the

Nazi regime: nearly 2,000 Jews were

freed—and were allowed to survive till the very end.

Leopold Gutterer, Goebbels’ deputy, told Stoltzfus that Goebbels ordered the Jews’ release “in order to eliminate the protest from the world, so that others didn’t begin to do the same.” Goebbels similarly decided not to arrest the protesting spouses in order to avoid the risk of further unrest from their non-Jewish relatives.

“We acted from the heart,” said one of them, the still

feisty Elsa Holzer. “We wanted to

show that we weren’t willing to let them go. I went to Rosenstrasse every day before work. And there was always a flood of people there.

It wasn’t organized or instigated. Everyone was simply there. Exactly like me.”

Though they are elderly and dwindling in number, there are

still eyewitnesses to tell the story, and Nathan Stoltzfus knows them all and

has already conducted audio-taped interviews with more than two dozen possible

participants in the documentary: women who protested, Jews who were imprisoned

and released, Jewish officials in charge of guarding the collection center.

Stoltzfus, who grew up in a Mennonite home and attended

Harvard Divinity School before becoming a Harvard-trained historian and a

Holocaust scholar, will himself be a major figure in the documentary.

When he began researching the story, there were only a small number of

short, anecdotal reports on the protest, which historians had tended to overlook

as an oddity without significance.

The documentary will be shot mainly in Germany, notably at

such key locations as the

In addition to eyewitness reports and scholarly analysis and

debate, the documentary will draw on photographs, newsreels, documents and

artifacts to visually tell the story: police release certificates for Jews set

free as a result of the protest; photographs of prisoners before and after their

ordeal; a chess board which a prisoner fashioned from a mattress cover, on which

he played with pebbles, to pass the time; pages from the Stürmer

publication, graphically illustrating the identity of half Jews; a report from

the main SS office of economics, announcing the arrival in Auschwitz of 25 Jews

deported from Rosenstrasse—who

twelve days later, following the protest, were returned to Berlin and released!

The documentary

would have aimed to provide the necessary historical

context for the Rosenstrasse protest and its improbable outcome: the German

defeat at Stalingrad, the heavy air attack on Berlin by the Royal Air Force, the

declaration of “Total War” by Goebbels and other top officials just the week

before. Goebbels’ decision will

be explored in terms of Hitler’s theory of power: many viewers will be surprised to realize that in Germany, terror was not

at all the main tool in the Nazi arsenal, though there is, in fact, a growing

consensus about this among historians.

Most movingly perhaps, the documentary

would have probed the

startling and effective loyalty of many Germans married to Jews. The story of the Rosenstrasse

Protest thus begins before that climactic event, with the stories of those who

protested, and how they came to marry Jews. It poignantly demonstrates the

courage—and the compromises—of their self-protective resistance, charting

the lives of intermarried couples in the context of Nazi persecution and social

harassment, as they are drawn slowly closer together, tighter and tighter, until

they meet at Rosenstrasse.

Despite the mounting and intense pressures on all sides, the

overwhelming majority of these mixed marriages continued.

At war’s end, no less than 98 percent of German Jews still alive in

Germany and registered with the police were married to non-Jewish Germans.

There are other examples that successful protest was

possible in Nazi Germany, and the documentary will touch on them, underscoring

that citizens everywhere bear responsibility for the actions of their

governments.

The documentary

would have been designed for a broad P. B. S.

television audience, as was the Chambon Foundation’s very successful first

undertaking, Weapons of the Spirit, which was introduced by Bill Moyers.

While maintaining high historical standards, the film will aim to make its points in ways that will be accessible to

many viewers, drawing on the inherent drama of the events in

question and the bittersweet consolation of the success that was achieved at Rosenstrasse.

The foundation, founded in 1982 by Pierre Sauvage, has

established itself as a growing media resource and archival facility focused on

the Holocaust and especially on its “necessary lessons of hope.”

The Chambon Foundation’s boards include many major historians and other

scholars, and its

projects draw on their expertise and advice.

Comments

on Nathan Stotzfus' Resistance of the Heart

Foreword by Joschka Fischer, then Foreign

Minister of Germany

Back

to Chambon Foundation

documentaries

[Varian Fry Institute] [Chambon Foundation Home] [Chambon Institute]

[email us] [contact information] [table of contents] [make a contribution?] [search] [feedback] [guest book] [link to us?]

© Copyright 2004, Chambon Foundation. All rights reserved. Revised: May 20, 2010