[Varian Fry Institute] [Chambon Foundation Home] [Chambon Institute Home]

Sunday Times Magazine (London), June 4, 2006

A Haven from Hitler, by Tim Carroll (online text at Sunday Times Magazine, without illustrations)

Text of article (see below) Article as pdf (large file)

The Sunday Times

June 04, 2006

Investigation

A haven from Hitler

The French village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon played an

extraordinarily courageous role in the second world war, providing sanctuary for

thousands of Jews. So why are the locals so reluctant to talk about it? Tim

Carroll investigates

The Massif Central in the Auvergne region of France has in recent years become a magnet for mountaineers, walkers and cyclists. Except for one village, whose occupants, for the past 60 years or so, have preferred to maintain a studious distance from outsiders.

Le Chambon-sur-Lignon is a haven of tranquillity, clinging to the edges of a plateau where the Haute-Loire meets the Ardèche. Perched 1,000 metres above the magnificent Rhône valley, Le Chambon’s community is remote and insular.

The municipal elders do their best to promote Le Chambon. But the locals – descendants of generations of hardy hill farmers – are indifferent to the financial benefits that the tourist trade might offer.

The centre of their village is a little run-down, with a few gnarled old cafes and restaurants. Not so unusual for a French provincial town. But Le Chambon is different. It has its own secret.

In a building at the crossroads of the village I am met by Pierre Sauvage, who was born here. This is the headquarters of his organisation, Amis du Chambon, which is dedicated to commemorating the town’s unique role in the second world war.

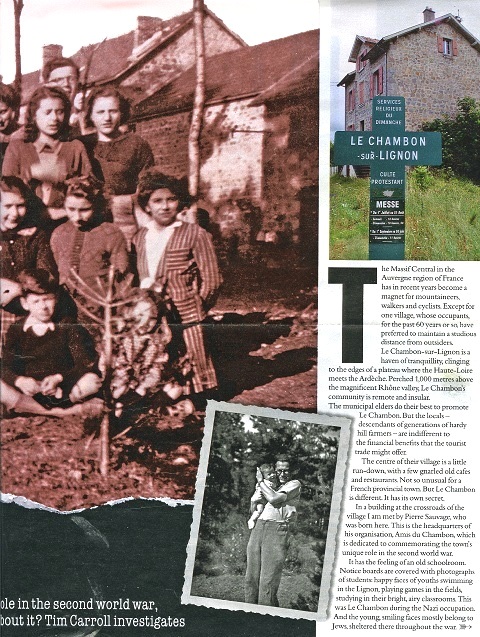

It has the feeling of an old schoolroom. Notice boards are covered with photographs of students: happy faces of youths swimming in the Lignon, playing games in the fields, studying in their bright, airy classrooms. This was Le Chambon during the Nazi occupation. And the young, smiling faces mostly belong to Jews, sheltered there throughout the war. Le Chambon-sur-Lignon is the village that said “non” to the Nazis and the Vichy regime set up in the wake of the fall of France. In 1940, when the French capitulated, the village, and a dozen or so of its near neighbours, was home to 5,000 people. By the end of the war those stout, country souls had saved the lives of 5,000 Jews. Virtually everybody on “the plateau” took part in the rescue effort. But Le Chambon is now acknowledged as the nucleus of this communal act of defiance, a beacon of hope and courage in the dark years of Vichy. In 1988, Israel’s Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial institute, hailed the wartime population of Le Chambon as among the “Righteous”. It is the only place in France to have been accorded such an honour.

It might be expected that in a country widely reviled for her

wartime collaboration with the Nazis, Le Chambon would be lauded as

evidence of a different side of the story. And to a certain extent it is.

President Jacques Chirac has belatedly seized upon the community as a “symbol”

of French wartime resistance: as the 60th anniversary of D-Day loomed, he

arrived in the village amid great fanfare and declared: “Here in adversity, the

soul of the nation manifested itself. Here was the embodiment of our country’s

conscience.”

But we all know that Le Chambon was unique. During the war the French were uncommonly compliant with their German masters. Out of about 300,000 Jews living in France at the time, around 75,000 were sent to their deaths in Nazi concentration camps. Historians generally agree that fewer than 5% of French people took part in even the most mild form of resistance. So rather than stir the soul of a nation where anti-semitism is still rife, Chirac’s words have provoked an uneasy disquiet. “There is nothing at all symbolic about Le Chambon as far as wartime France goes,” says Sauvage. “Quite the contrary: it was the exception in a country that overwhelmingly submitted to the Nazi regime.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pierre Sauvage was born on the plateau in the dying days of the war. His Jewish father, Léopold Smotriez, was born in Germany but raised in France. His mother, Barbara, was a Polish Jew. They lived in Paris but fled to Marseilles after the Germans invaded, and adopted the French-sounding pseudonym Sauvage. When Barbara became pregnant, the couple were steered to Le Chambon by a friend. They were fortunate. Throughout the Nazi occupation, a doctor by the name of Roger Le Forestier tended to the medical needs of the people on the plateau, and he shared their humanitarian outlook.

On March 25, 1944, he delivered a baby boy to the Sauvages. After the war the family immigrated to the US, where Léo became the New York correspondent of Le Figaro. Pierre Sauvage was raised in the city, unaware of his Jewish heritage or that he was a survivor of the Holocaust. “I knew I was born in Le Chambon,” he says. “But there was nothing in the home or in my parents’ conversations to indicate what they had been through.” It was not until he was 18, when he went to Paris to study at the Sorbonne, that he was told the truth. But for the time being, the story of Le Chambon remained little more than an occasional twitch in his subconscious. Eventually, Sauvage found his vocation in the cinema and became an award-winning film-maker.

In 1982 he was drawn back to the remote community of his birth. He decided to make a film about Le Chambon. Over several years he filmed those who had been involved in rescuing the Jewish children. While listening to their testimony, he discovered something singular about the plateau. In an overwhelmingly Roman Catholic country, the area’s inhabitants were predominantly Protestant. The first Protestants in France had long suffered murder at the hands of their countrymen. Many fled the country. But here they clung tenaciously to their rocky territory – and their equally unshakable beliefs.

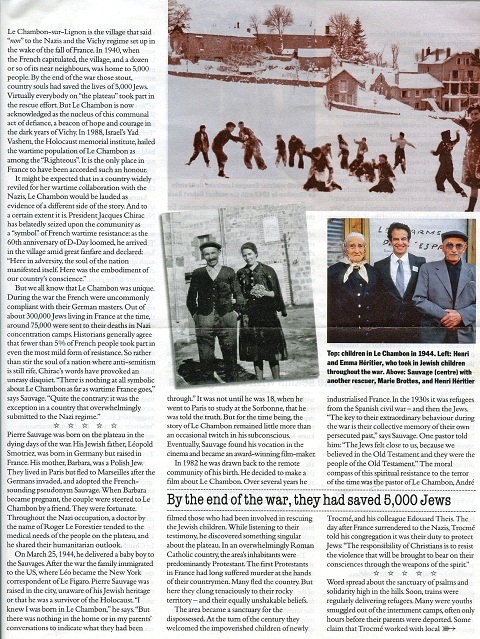

The area became a sanctuary for the dispossessed. At the turn of the century they welcomed the impoverished children of newly industrialised France. In the 1930s it was refugees from the Spanish civil war – and then the Jews. “The key to their extraordinary behaviour during the war is their collective memory of their own persecuted past,” says Sauvage. One pastor told him: “The Jews felt close to us, because we believed in the Old Testament and they were the people of the Old Testament.” The moral compass of this spiritual resistance to the terror of the time was the pastor of Le Chambon, André Trocmé, and his colleague Edouard Theis. The day after France surrendered to the Nazis, Trocmé told his congregation it was their duty to protect Jews: “The responsibility of Christians is to resist the violence that will be brought to bear on their consciences through the weapons of the spirit.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

Word spread about the sanctuary of psalms and solidarity high in the hills. Soon, trains were regularly delivering refugees. Many were youths smuggled out of the internment camps, often only hours before their parents were deported. Some claim that Trocmé worked with local resistance groups. But this is fiction. Christian relief groups got them out. They were funded by American, Swiss and French charities; Quakers and American Congregationalists; Evangelists – and Catholics. Within months there were a dozen schools and scores of homes helping to cater for this tidal wave of hounded humanity. In flagrant violation of Vichy decree, the children were not obliged to swear obedience to Marshal Pétain. Nor did the church bell ring in honour of his accession, as it was required. Pensions and hotels were bursting at the seams with strange faces. What visitors must have made of all of this is a mystery. “They didn’t blend in at all,” laughs Nelly Trocmé Hewett, the pastor’s daughter, who grew up in Le Chambon and now lives in the US. “They were all obviously Jewish,” she says. Those less well disposed to Le Chambon knew it as “the nest of Jews in Protestant country”.

But the town’s reputation seemed not to have reached the higher echelons of the Vichy regime. In the late summer of 1942, the minister of youth in Pétain’s cabinet, Georges Lamirand, arrived on a propaganda mission. He brought with him the local prefect, Robert Bach, whose responsibilities included the deportation of Jews. A welcome was staged, at which Lamirand, addressing a crowd of youths, ended with the Vichy flourish: “Long live Marshal Pétain!” It was greeted by total silence, until a Salvation Army volunteer said: “Long live Jesus Christ!” A young man handed Lamirand a letter. It read: “We feel obliged to tell you that there are among us a certain number of Jews.” The letter stated that any Jews would be protected. Lamirand objected that the treatment of Jews was not his responsibility. It was that of the prefect, Robert Bach, he said, referring to the man at his side. Bach said nothing. Several weeks later a convoy of gendarmes arrived, bringing three empty buses for their presumed prisoners. But there were no Jews to be found. They had been hidden away in the hills and forests and remote mountain farms. The gendarmes stayed for three weeks, as the Jews were moved from one hiding place to another. Their hapless pursuers were finally shamed into submission.

“It is a horrible thing we have to do,” confessed one policeman. They left, the buses still empty. Vichy’s failure to challenge a small, peaceful community that openly rebelled against it betrayed the cowardly nature of Pétain’s regime.

It might have been expected, however, that Le Chambon would face a more formidable foe when German forces swept into the “unoccupied zone”?of Vichy France in November 1942. But even though the Germans managed to fill two hotels in Le Chambon with their soldiers, nothing seemed to change. By then, the French gendarmerie seemed to have become intoxicated by the air of Le Chambon. On their excursions to the plateau, the police would head straight for a particular hotel restaurant. Over lunch, the men proceeded to discuss loudly which properties they were scheduled to search that afternoon. By the time they arrived, their quarry had gone.

Le Chambon did not escape every depredation of the Nazi peril. In 1943, two dozen Jewish students were arrested and deported. Five months after Pierre Sauvage was born, the man who delivered him was murdered by Klaus Barbie’s Gestapo. Roger Le Forestier’s battered corpse was piled on a heap with 119 resistance fighters and burnt. But tragic as these deaths were, they were trivial compared with the obscenities of the time. Not far away, after all, at Oradour-sur-Glane in June 1944, a village of 642 men, women and children was massacred. Yet unlike Le Chambon, Oradour-sur-Glane had not taken any part in the resistance. There was another puzzle. In early 1943, André Trocmé and Edouard Theis were taken away by the French gendarmes along with the headmaster of the public school. They were thrown into an internment camp to await deportation. Yet several weeks later they were returned to the village, unharmed. Nobody knew how they had escaped a grislier fate.

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Who can explain the miracle of Le Chambon?” asks Sauvage. “What is most remarkable about these people is, they didn’t think they were doing anything remarkable.” It explains in part why the people of Le Chambon have displayed so little interest in Sauvage’s memorial project. (Though it might equally be resentment at someone from across the Atlantic “hijacking” Le Chambon’s historical conscience. “We have our own culture,” says Mayor Francis Valla, who points out that the town has its own plans for a museum.)

The wider French population is equally ambivalent. When Sauvage’s critically acclaimed documentary about Le Chambon was shown on French TV in 1989, it was broadcast in the dead of the night. Sauvage purchased an old farmhouse in Le Chambon some years ago, with the intention of renovating it and establishing a more fitting memorial to the villagers than the old shop where we first met. But his efforts to enrol help have been greeted with a lack of interest. And only days after meeting me last summer, he was turned down for European Union funding. One reason for the disdain, he muses, is that the heroes of the action were non-mainstream Protestants. But he suspects that the modern French state is more disturbed by Le Chambon’s challenge to the pre-eminence of “les valeurs de la République”: the values of the Republic, and the upholding of the virulently anti-religious style of secularism known as laïcité. “For the French, while they tip their hat off to Le Chambon, it represents two values they mostly hold in contempt: communautarisme, that sense of narrow identity that the French are constantly urged to transcend, and religious beliefs.” Chirac pointedly refused to go to Pastor Trocmé’s church during his visit.

Sauvage is quick to emphasise that three-quarters of all French Jews were saved from the Nazis. “Lots of people must have been doing the saving,” he says. “The vast majority of people weren’t murderers. They were simply apathetic. They found ways of ducking the issue.” When Sauvage was making his film, he managed to catch up with Georges Lamirand. Though charming, Lamirand emerged almost as a caricature of the preening, self-justifying bureaucrat. Confronted by Sauvage about the 75,000 Jews who were sent to their deaths by his regime, Lamirand once more passed the buck to the prefect Robert Bach, as he had done in the village that summer’s day of 1942. “Some of my best friends are Jews,” he said, lamely. But Sauvage had made an intriguing discovery during his research: some papers dated March 4, 1943, shortly after Trocmé, Theis and the headmaster had been arrested. In them, a Vichy official based in Le Puy-en-Velay strongly urges his superiors to release the three men. He assures them his investigations have shown that the accounts of Jews in Le Chambon were grossly exaggerated, and the number of refugees was “relatively minimal”. The fading document is signed by the prefect for Haute-Loire, Robert Bach. The Lord works in strange ways, as Pastor Trocmé himself might have said.

As for Pierre Sauvage, he is at a loss for words. Turned down by the European Union and ignored by the French, he is having to fund the exhibition and farmhouse out of his own pocket. He spends much of his time travelling around the US, speaking to willing audiences about the remarkable community he owes his life to. Yet he finds indifference on our side of the Atlantic. He is disturbed by the way the “challenge” that Le Chambon presents to France risks being buried in Chirac’s praise. “Many Christians still have to face the magnitude of their failure during the Holocaust,” he says. “But to be able to see what it was possible to do in those dark times, they need an example against which they can measure themselves. Le Chambon is that example – of what an entire community was able to do. Yet no one seems to want to honestly acknowledge the reasons why.”

Copyright 2006 Times Newspapers Ltd.

[Varian Fry Institute] [Chambon Foundation Home] [Chambon Institute]

[email us] [contact information] [table of contents] [make a contribution?] [search] [feedback] [guest book] [link to us?]

© Copyright 2005, Chambon Foundation. All rights reserved. Revised: May 20, 2010